On February 5, 2019, over 1.1 million public school students in New York City will be happy to have a day off to observe the Lunar New Year. It’s been a tradition since the City officially made it a public holiday in 2016.

While China is not the only one celebrating the Lunar New Year (many Asian cultures including Japan, Korean, Laos, Singapore, Nepal, Tibet, Vietnam, etc. all celebrate the Lunar New Year with variations), Chinese lunar calendar was already created during the 14th Century B.C. according to the Oracle Bones ( 甲骨文, jiǎ gǔ wén), China's oldest written records. Some even posit it started with China’s legendary Yellow Emperor (黄帝, huáng dì) in 2637 B.C. While today in China the western calendar, which the Republic of China adopted in 1912, effectively regulates Chinese daily life and work, traditional holidays and festivals still follow the lunar calendar, or 阴历(yīn lì), literally translated as “yin calendar”.

According to the Chinese lunar calendar, each year is named after one of the 12 zodiac animals: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig. There are many stories about how the 12 animals are chosen (see this delightful and very educational unit on TED-Ed, including a video, a fun quiz, and resources for digging deeper). Every Chinese knows his or her zodiac sign. For any baby born on and after February 5 in 2019, or anyone born in 1935, 1947, 1959, 1971, 1983, 1995, and 2007, he or she is a pig or the 属相(shǔ xiàng,zodiac sign) is Pig,(猪,zhu). Chinese would simply say “他(她) 属猪” (tā shǔ zhu,his/her zodiac sign is the pig.)

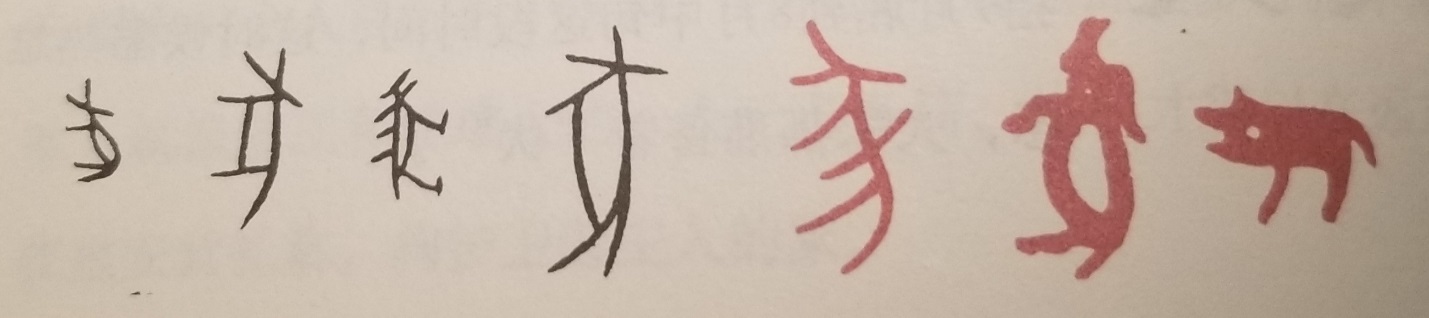

The fact that the pig is one of the 12 zodiac animals spotlights its historical importance in Chinese culture. Traditionally, pigs are one of the earliest domesticated animals in China, and have been closely linked to the livelihood in agrarian societies. Look carefully, the bottom part (豕)for the word “family”, 家(jiā),pictographically represents a pig.

|

Various early forms of the word "pig" (豕) in Chinese.

Source: “China: Empire of Living Symbols", by Cecilia Lindqvist, 1989

While there are many cultural characteristics and symbolic meanings associated with pigs, in China they represent wealth and treasure.

In terms of language, 恭喜发财 (gōng xǐ fā cái or “Kung Hei Fat Choi”, its Cantonese pronunciation, roughly translated as “wish you make a fortune”), probably is best known to New Yorkers. The Analects (论语,lún yǔ ), a classics compiling sayings of Confucius ( 479 - 551 B.C.), writes, “恭,近于礼;喜,犹福也。” (gōng, jìn yú lǐ; xǐ, yóu fú yě), explaining 恭 is similar to “respect”; 喜 equals “blessing”. Thus 恭喜 together literally means “a blessing with respect”. However, 恭喜发财 as a Lunar New Year greeting didn’t gain popularity until early 20th century after Westerners forced interactions with the Cantonese. In addition, Chinatowns all over the U.S. were first built by Chinese immigrants mostly from Canton, which probably explains if there is only one Chinese Lunar New Year greeting known to Americans, it’s likely “Kung Hei Fat Choi”. That said, it’s probably time to expand the vocabulary:

吉祥如意(jí xiáng rú yì): In The I Ching ( 易经,yì jīng, or Book of Changes), a Chinese classics from around 10 Century B.C., 吉 indicates an auspicious and positive sign when performing divination. 祥 carries a similar meaning as 吉. 如意 literally means “as you wish”. The expression basically can be translated as “Have an auspicious year as you wish.”

恭贺新禧 (gōng hè xīn xǐ): 恭贺 means “to congratulate respectfully”;新 means “new; 禧 means “auspiciousness and happiness”. The expression essentially means “Wish you a happy and auspicious new year.” (You can never get too much auspiciousness and happiness for the new year, right?)

While in New York, Chinese New Year is always a significant event, Traditionally Chinese start their celebration of Chinese New Year, or the Spring Festival (春节,chūn jié), during the Lunar December, the 12th (and the last) month of the lunar new year. POn the 8th day of the month, people cook a special congee, or rice soup, with 8 grains/nuts (腊八粥, là bā zhōu ), and; on the 23rd or 24th, they“send away” the “Kitchen God” residing with the household during the year with offerings, especially candies (so they will speak sweetly about the household in the Gods’ report to the heavenly gods). After the Kitchen God has departed, those left on Earth continue the preparation of welcoming the New Year through a thorough cleaning of the house, purchasing new clothing and getting a haircut for themselves before the actual New Year’s Eve, or 除夕 (chú xī).

除夕(chú xī) is the peak of the celebration! All family members come together to feast on traditional dishes like fish, dumplings, meatballs, rice cakes, among many other delicious foods. Families sit together past midnight to send off the old year and welcome the new year with happiness, strength, and wealth.

Today, 除夕is all about family reunion and happiness. However, if we look a little deeper, it isn't always so festive. 除 means “time passed”, 夕 means “the time of dusk”. In the Book of Songs (诗经,shī jīng)from 11 - 6 Century B.C. (yet another very ancient literature), a poetic expression says the following:

“今我不乐,岁月其除” (jīn wǒ bù lè, suì yuè qí chú)

Translation: Right now if I don’t get to enjoy (time), months and years are passed.

For Chinese, 除夕 could indeed be a melancholy occasion to contemplate the insignificance of the individual life compared to the changing and passage of time. It perhaps explains in part why spending time with families with lots of food, overly joyful activities, and giving youngsters red envelopes are needed to counter such feelings of helplessness. Not surprisingly, many Chinese poems about the Lunar New Year are not so celebratory either, especially if the poet happened to be away from home. One poem I like is by 王湾 (wáng wān, 693-751 A.D.), a poet who is only remembered perhaps by his poem on the Lunar New Year:

Title: 次北固山下 (cì běi gù shān xià)

客路青山外, (kè lù qīng shān wài)

行舟绿水前. (xíng zhōu lǜ shuǐ qián)

潮平两岸阔, (cháo píng liǎng àn kuò)

风正一帆悬. (fēng zhèng yī fān xuán)

海日生残夜, (hǎi rì shēng cán yè)

江春入旧年. (jiāng chūn rù jiù nián)

乡书何处达, (xiāng shū hé chù dá)

归雁洛阳边. (guī yàn luò yáng biān)

Translation:

Title: Stopping By Mount Beigu

As a guest, I pass by the lush mountain,

Riding a boat in the green water.

Tides full, the river banks are wide,

Wind straight, the sail hangs upright.

Born out of the lingering night, the sun rises above the ocean;

Into the passing year, the river carries the spring.

In what place would my letter to home arrive?

Luo Yang, where the wild geese return to.

We know that Wang Wan is from Luo Yang, an ancient northern city where mountains would be barren in winter. Away from home when the first sunshine of the new year breaks the lingering darkness, Wang Wan appears to be sensible yet not overly consumed by loneliness. Instead, picturing himself surrounded by the vast river with full yet calm waves, the rising sun, the mountain still thriving, his poem is perfectly uplifting in connecting the individual human and the greatness of the nature. 海日生残夜, 江春入旧年. (hǎi rì shēng cán yè, jiāng chūn rù jiù nián), has become one of the most celebrated lines describing the beginning of the new year.

We encourage you to take advantage of all the cultural experiences China Institute and other organizations and groups across New York are currently preparing. Beyond just a dragon boat and lion dance, look to the holiday as an opportunity to learn more about one of the world’s richest cultures in the midst of the world’s most vibrant and exciting city.

Learn more about the China Institute's Chinese New Year Day Camp HERE, and more about their enrichment classes HERE.

Related articles:

Enrichment Classes in Lower Manhattan

Educational Directors of Lower Manhattan

List of Preschools in Lower Manhattan

Macaroni Kid Lower Manhattan is the family fun go-to source for the latest and most comprehensive information in our area. Subscribe for FREE today.